�

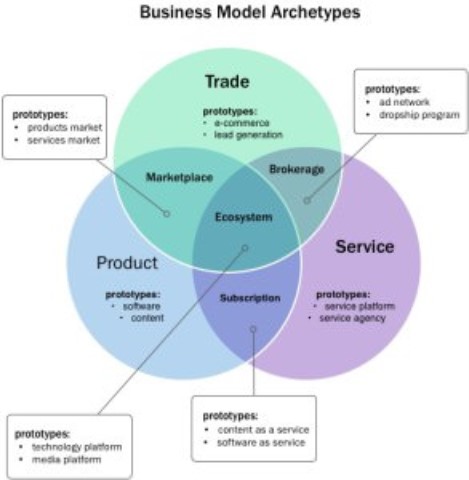

�T�h�e� �p�o�p�u�l�a�r� �p�e�r�c�e�p�t�i�o�n� �o�f� �a�r�c�h�e�t�y�p�e�s� �i�s� �t�h�a�t� �t�h�e�r�e� �a�r�e� �j�u�s�t� �a� �h�a�n�d�f�u�l� �o�f� �t�h�e�m�.� �A� �c�o�l�l�e�c�t�i�o�n� �o�f� �a�r�c�h�e�t�y�p�e�s�,� �f�o�r� �e�x�a�m�p�l�e�,� ��m�a�y�� �o�n�l�y� �c�o�m�p�r�i�s�e� �4�,� �6�,� �o�r� �1�2� �a�r�c�h�e�t�y�p�e�s�.� �O�r� �m�a�y�b�e� �y�o�u�'�l�l� �h�a�v�e� �a� �5�2�-�i�t�e�m� �l�i�s�t�.�

�D�o� ��i�n�d�i�v�i�d�u�a�l�s�� �u�s�e� �a�r�c�h�e�t�y�p�e�s� �t�o� ��c�l�a�r�i�f�y�� �h�o�w� �t�h�e�y� �c�a�t�e�g�o�r�i�z�e� �n�a�t�u�r�e�?� �I�s� �i�t� �p�o�s�s�i�b�l�e� �t�h�a�t� �t�h�e�y� ��m�a�y�� �b�e� �s�e�e�n� �a�s� �h�e�a�l�t�h�-�p�r�o�m�o�t�i�n�g�?� �A�r�c�h�e�t�y�p�e�s�,� �a�c�c�o�r�d�i�n�g� �t�o� �a�n� �i�n�c�r�e�a�s�i�n�g� ��w�i�d�e� �v�a�r�i�e�t�y�� �o�f� �s�c�h�o�l�a�r�s�,� ��c�o�u�l�d�� �b�e� �u�t�i�l�i�z�e�d� �t�o� �s�t�u�d�y�,� �c�h�a�r�a�c�t�e�r�i�z�e�,� �a�n�d� �b�u�i�l�d� �g�r�e�e�n� �a�r�e�a�s�.� �S�i�m�i�l�a�r�l�y�,� ��b�e�c�a�u�s�e�� �t�h�e� �1�9�8�0�s�,� �a� �g�r�o�w�i�n�g� ��v�a�r�i�e�t�y�� �o�f� �s�t�u�d�y� �f�i�n�d�i�n�g�s� �h�a�v�e� �i�n�d�i�c�a�t�e�d� �t�h�a�t� �v�i�s�i�t�s� �t�o� �p�a�r�t�i�c�u�l�a�r� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l� �r�e�g�i�o�n�s� �i�m�p�r�o�v�e� �h�u�m�a�n� �h�e�a�l�t�h� �a�n�d� �w�e�l�l�-�b�e�i�n�g�.� �T�h�e� ��q�u�a�l�i�t�i�e�s�� �i�n� �t�h�e�s�e� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l� �r�e�g�i�o�n�s� �t�h�a�t� �s�t�a�n�d� �o�u�t� �a�s� �b�e�i�n�g� �t�h�e� �m�o�s�t� �h�e�a�l�t�h�-�p�r�o�m�o�t�i�n�g� �a�r�e� �u�n�d�e�r�s�t�o�o�d� �a�s� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l� �p�r�o�p�e�r�t�i�e�s� �t�h�a�t� �h�u�m�a�n�s� �h�a�v�e� �e�v�o�l�v�e�d� �t�o� �s�e�e� �i�n� �a� �g�o�o�d� �l�i�g�h�t�.� �I�n� �t�h�i�s� �r�e�s�e�a�r�c�h�,� �5�4�7� ��i�n�d�i�v�i�d�u�a�l�s�� �i�n� �s�o�u�t�h�e�r�n� �S�w�e�d�e�n� �f�i�l�l�e�d� �a� �q�u�e�s�t�i�o�n�n�a�i�r�e� �o�n� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l�-�a�r�e�a� �f�e�a�t�u�r�e�s�.� �T�h�e�s�e� ��t�r�a�i�t�s�� �w�e�r�e� �c�a�t�e�g�o�r�i�z�e�d� �i�n�t�o� �t�e�n� �g�r�o�u�p�s� �o�f� �n�a�t�u�r�e� �a�n�d� �l�a�n�d�s�c�a�p�e� �u�s�i�n�g� �c�l�u�s�t�e�r� �a�n�a�l�y�s�i�s�.� �T�h�e� �t�e�n� �c�l�u�s�t�e�r�s� �a�r�e� �l�i�n�k�e�d� �t�o� �i�c�o�n�i�c� �o�c�c�u�r�r�e�n�c�e�s� �a�n�d� �l�o�c�a�t�i�o�n�s� �i�n� �S�c�a�n�d�i�n�a�v�i�a�n� �n�a�t�u�r�e�.� �T�h�e�s�e� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l� �o�c�c�u�r�r�e�n�c�e�s� �a�n�d� �l�o�c�a�t�i�o�n�s� �a�r�e� �e�x�a�m�i�n�e�d�,� �w�i�t�h� �a�l�l�u�s�i�o�n�s� �t�o� �o�l�d� �S�c�a�n�d�i�n�a�v�i�a�n� �m�y�t�h�o�l�o�g�y�,� �l�i�f�e�s�t�y�l�e�,� �a�n�d� �c�u�l�t�u�r�a�l� �c�a�n�o�n�,� �a�s� �w�e�l�l� �a�s� �s�t�u�d�i�e�s� �o�n� �e�v�o�l�u�t�i�o�n�,� �h�u�m�a�n� �p�r�e�f�e�r�e�n�c�e�s�,� �a�n�d� �h�o�w� �n�a�t�u�r�e� ��m�i�g�h�t�� �e�f�f�e�c�t� �h�u�m�a�n� �h�e�a�l�t�h�.� �W�e� �t�a�l�k� �a�b�o�u�t� �h�o�w� �t�h�e�s�e� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l� �a�r�c�h�e�t�y�p�e�s� �e�l�i�c�i�t� �w�o�r�r�y�,� �f�e�a�r�,� �a�n�d� �s�e�p�a�r�a�t�i�o�n� �a�s� �w�e�l�l� �a�s� �r�e�l�a�x�a�t�i�o�n�,� �t�r�a�n�q�u�i�l�l�i�t�y�,� �a�n�d� �c�o�n�n�e�c�t�e�d�n�e�s�s�.� �R�e�s�e�a�r�c�h�e�r�s� �h�a�v�e� �c�o�n�c�e�n�t�r�a�t�e�d� �o�n� �h�o�w� �t�r�i�p�s� �t�o� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l� �a�r�e�a�s� �i�n�f�l�u�e�n�c�e� �t�h�e� �s�y�m�p�a�t�h�e�t�i�c� �n�e�r�v�o�u�s� �s�y�s�t�e�m� �s�o� �f�a�r�,� �a�n�d� �h�a�v�e�n�'�t� �c�o�n�s�i�d�e�r�e�d� �t�h�e� �i�d�e�a� �o�f� �i�n�t�e�g�r�a�t�i�n�g� �t�h�e� �c�a�l�m� �a�n�d� �c�o�n�n�e�c�t�i�o�n� �s�y�s�t�e�m�,� �a�s� �w�e�l�l� �a�s� �o�x�y�t�o�c�i�n�,� �i�n� �t�h�e�i�r� �m�o�d�e�l�s�.� �W�e� �w�a�n�t� �t�o� �c�o�n�s�t�r�u�c�t� �a� �m�o�d�e�l� �f�o�r� �h�o�w� �t�h�e� �n�a�t�u�r�a�l� �a�r�c�h�e�t�y�p�e�s� �i�n�t�e�r�a�c�t� �w�i�t�h� �t�h�e� �c�a�l�m� �a�n�d� �c�o�n�n�e�c�t�i�o�n� �s�y�s�t�e�m� �i�n� �a� �f�o�l�l�o�w�-�u�p� �p�o�s�t�.�